ESSAY/OPINION

Down the hill, up the hill…

the architecture of Lisbon’s alternative culture

PhD (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne), Architect (IST) and associate researcher at the laboratory of urban sociology (Lasur, EPFL)

The last decade has witnessed an aestheticizing process central Lisbon’s “alternative” cultural spaces. Offering new uses for pre-existing structures, these projects function through erratic specific spatial transformations in the buildings that they occupy, often having a considerable impact on the alteration of uses of the surrounding urban space.

Historically, the mutation of building’s functions is one of the more frequent interventions in spaces. Old abandoned or obsolete structures frequently take on new uses adapted to new times. The economic factor is, without a doubt, one of the main motivators of this type of change. Currently, there is an unprecedented level of investment in tourism, and it is in this context that Lisbon’s centre is undergoing an intense process of touristification that is visible to all. However, the city has already gone through another similar process in previous decades, in terms of tertiarization, where for example, many residential buildings were replaced with offices and cafés and transformed into banks. It was a moment in which the Metropolitan Area of Lisbon grew and a great part of its population moved to the periphery.

This investment in tourism, which is regarded as an important source of economic revenue for a country in crisis, requires spatial and architectural transformations to host the foreign visitor. Thirsty for local traditional culture — ranging from the historical monument, the image of Fernando Pessoa, the pastel de nata or a cuisine that exalts the sardine —, tourist satisfaction requires the mass industrial production of corresponding images. These start to function as symbols of the paradoxical glocal (global + local) spirit, resulting in the banalization of the contents of those “typical objects”.

This current fashionable trend was succeeded by a practical application in terms of urban policies, the idea of the “creative city” (Florida, 2002; Landry, 1995, 2006), which suggests that the promotion of the arts and culture is fundamental for the economy and the social and territorial dynamics of the city.

The value given to image has increased exponentially and its impact on architecture has also gained importance. After a long period of economic progress during which so many star-architectures were created and built and so many buildings were demolished and substituted, the time came to function with a less favourable economic situation, thus adapting architectural production to available means. “Re-Architecture” — the Reutilization, Rehabilitation, Recycling and Revitalization of buildings, a term partly coined by the architect Sherban Cantacuzino (Re-Architecture: Old Building / New Uses, New York: Abbeville Press, 1989) – gained supporters, becoming the centre of attention of many architects and even of some clients. Originally encouraged by ecological or social justice concerns, this is also an architecture of Resistance (when not deviated by lucrative interests).

These re-architectures gain particular relevance in projects linked to the arts, culture and creative professions 1. If on the one hand there has been a massive emergence of hotels in the city centre during the last few years, on the other, there have also appeared various small or medium-sized cultural spaces throughout Lisbon. Many of these projects used “re-architecture” types of spatial practices and visual environments inspired by symbols used for anti-capitalist struggles, counter-cultures and underground universes (i.e., of a fringe cultural nature).

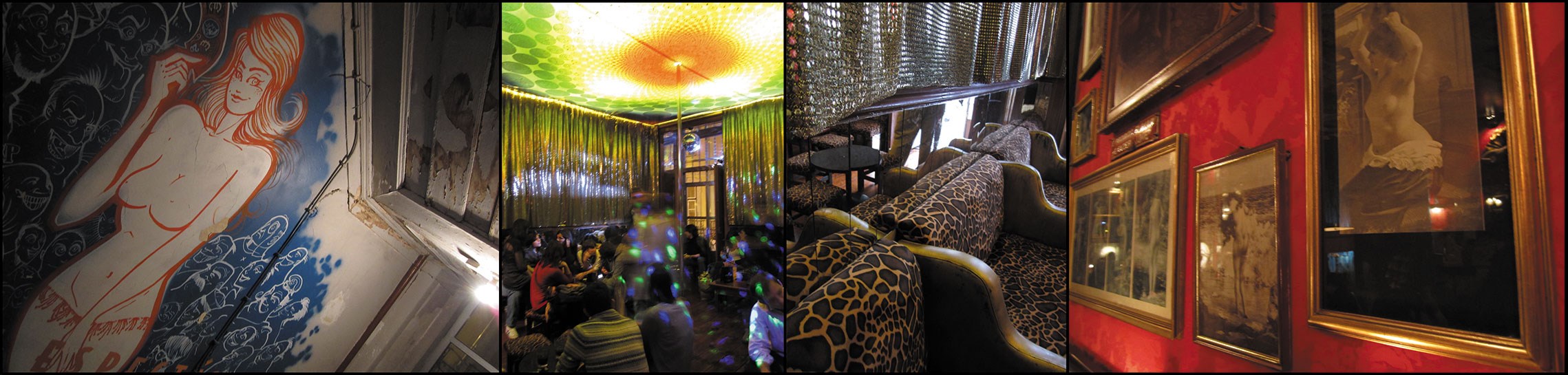

If the image of Che Guevara, commercialized and reproduced (t-shirts, key-chains, etc.), gradually lost its meaning of resistance and struggle, becoming banal, then the same has happened with the environments of co-called “alternative” cultural spatial projects. An increasing number of spaces are created to seem “alternative”, i.e., conceived in terms of image, form and programme to attract a certain type of visitor and client, with tastes geared towards the arts and/or counter-cultures 2. Thus, colourful spaces and appealing spatial environments are created to produce a certain effect for the visitor, as is the case of the inescapable Pensão Amor — which includes a bar, concert room, co-working space, bookstore and shops. Pensão Amor was created by the Mainside real estate agency, which decided to maintain the local pre-existing underground feel, populated by prostitutes and sailors, while recreating and romanticizing it through the painting of murals (in a street art/comic book style). This décor and concept is the delight of a bohemian and relatively wealthy Lisbon, and above all of the tourist, in what was once a “casa de meninas” (brothel) – the name “Pensão Amor” (Love Inn), fatally alludes to the memories and uses of another time. On the other hand, the stairwell was kept in its degraded state on purpose, with peeling paint allowing glimpses of the multiple construction layers of the interior of the walls. As if the derelict state of the building were actually something desirable that contributes to its general charm. The aesthetic of recycling and nostalgia is therefore present in the objects, the memories and the architecture of the building itself.

© Letícia do Carmo

In a design or environment project there is an aesthetic manipulation that, allied with the effects of everyday occupation and the decoration of the space can lead to the development of an aestheticizing process. In turn, this process can result in a somewhat artificial environment. If the sensorial stimulation of the visitor tends to originate a certain “aesthetic pleasure” mentioned by the philosopher Gernot Böhme (Atmosphere as the Fundamental Concept of a New Aesthetics, SAGE, 1993, p.125), when taken to the extreme, this aestheticizing or ornamentation process can be used to entertain and manipulate the “masses”, a phenomenon criticized by Siegfried Kracauer during the 1930’s, between wars, through his disenchanted vision of modern civilization (L'Ornement de la masse – Essais sur la Modernité Weimerienne, Paris: La Découverte, 2008 [1920s-1930s]).

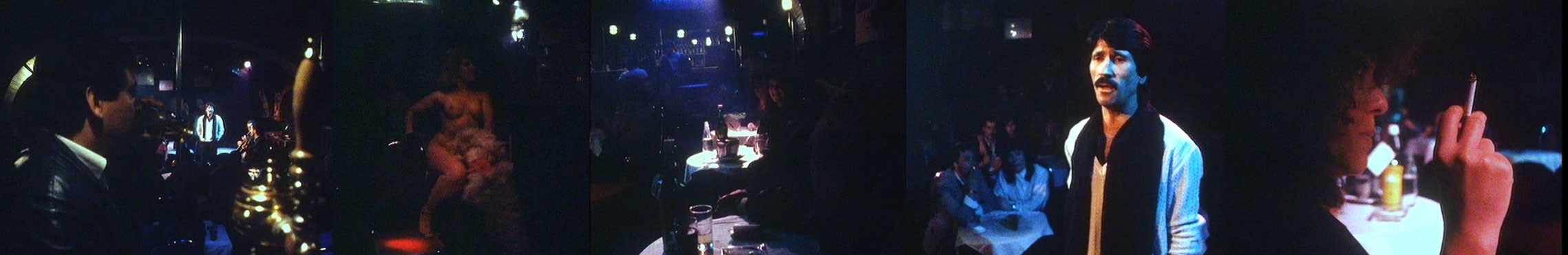

Left: image from a vídeo by Vítor Gabriel (https://vimeo.com/34970118)

© Letícia do Carmo

The success of Pensão Amor extended the phenomenon to the rest of the street, painted (and baptized) in pink and invaded by new luminous bars, which have gradually replaced the old ones that had a truly subversive nature. Today, there is an apparently constant atmosphere of happiness on Rua Nova do Carvalho, both day and night, sponsored by a well-known brand of vodka. As the philosophers Lipovetsky and Serroy forewarn (L’Esthétisation du Monde – Vivre à l’Âge du Capitalisme Artiste, France: Gallimard, 2013, p.12), the aesthetic-emotional dimension shifted to the centre of the competition between brands, used for profitable ends.

Located on the terrace of the chic and sunny Santa Catarina and Chiado hill, the dark and underground Cais do Sodré, more precisely the two streets that pass under the Rua do Alecrim, underwent a profound and rapid transformation in terms of their uses 3 through the impact and partial influence of a project. This area stopped being associated with drug use and prostitution, to be associated with a festive and young environment, while maintaining the status of an area for night-life and entertainment.

The second great propeller of this change is related to the changes made to Renting Laws in 2012, which made many of the degraded buildings of this central area available for the market, attracting the attention of investors. Another important factor is the fact that Cais do Sodré began to take in a considerable part of Bairro Alto’s nightlife.

For decades, Bairro Alto was one of the most attractive neighbourhoods for lisboners, due to its intense night life (bars, restaurants, cultural spaces 4, printers) and its daytime activity, mainly associated with the presence of small shops and traditional commerce and the strong ties established between the residents of the neighbourhood. It had many of the ideal conditions of Florida’s “creative city”: a past with a dubious reputation, followed by the arrival of bohemians and artists, a considerably abundant social mixture (which included a local population from a “traditional” social structure as well as a strong homosexual community), a mixture of professional strata and services and an intense street life. This “street level culture” is precisely what Florida (2002, p.182) considers as essential for a neighbourhood to be “cool and attractive”.

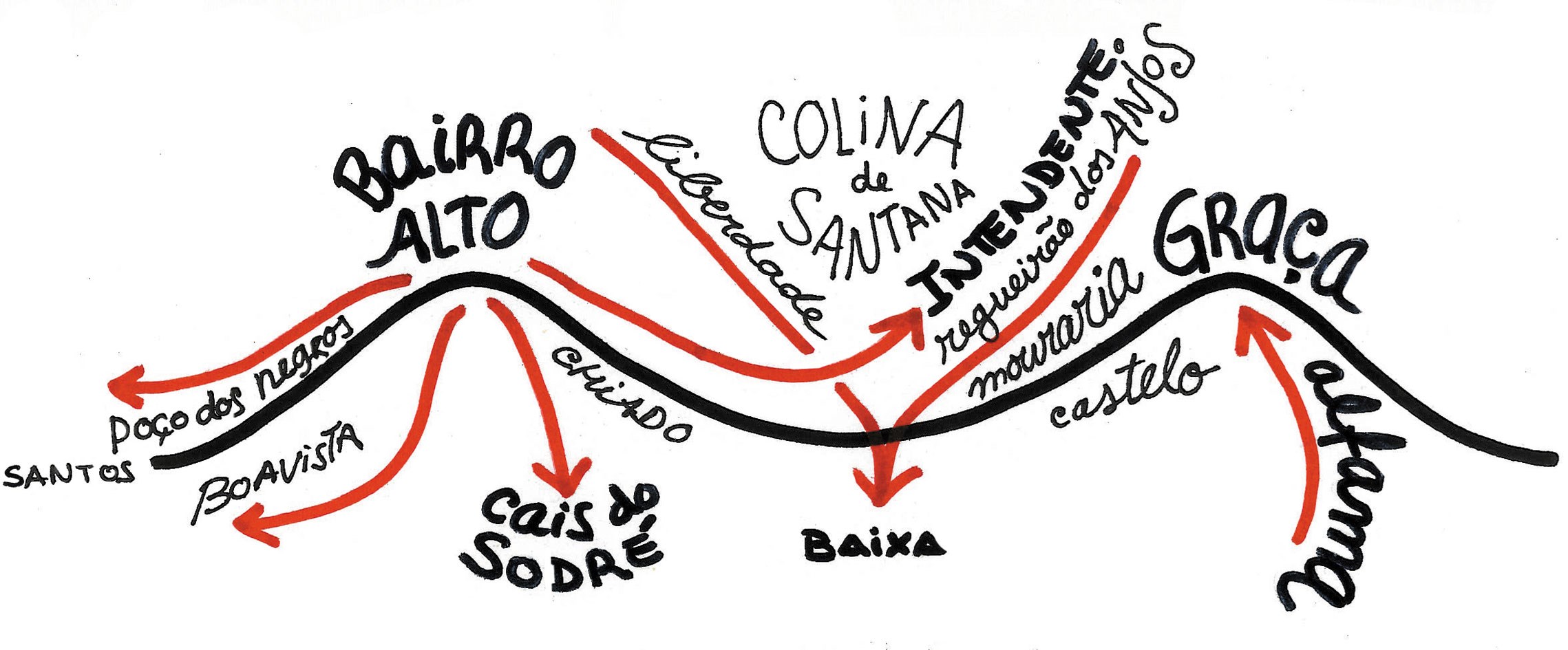

Bairro Alto’s “ecosystem” became saturated due to various factors: excessive popularity, people, noise and garbage, and consequently, the negative reactions of residents, as well as an increased interest in real estate and tourism. The result was a tighter control on the opening hours of bars, limitations for automobile traffic inside the neighbourhood, heavier policing and video-surveillance. Disgruntled, bohemian lisboners went in search of new pastures, travelling down the hill to Cais do Sodré, to Rua de São Paolo, to Poço dos Negros, or even to Intendente. A way of life that was once concentrated essentially in one area, but distributed throughout the entire neighbourhood (which with its narrow streets and relatively accidental topographical characteristics created the illusion of an irregular plan, giving it a labyrinth-like character), was dispersed across various different axis:

• Rua do Alecrim and Bica to Cais do Sodré and Rua de São Paulo;

• Calçada do Combro to Rua do Poço dos Negros, connecting with the Santos area;

• Chiado (Rua Garret), extending into Baixa and arriving at Martim Moniz and Intendente.

A network was created across a considerable part of the city, encompassing not only bars, but also co-working spaces connected to creative areas, as well as others involving more experimental artistic projects, collective platforms or cultural and socio-cultural associations 5. Similarly to what happened with Bairro Alto, these areas are undergoing a process of gentrification. However, unlike that neighbourhood, where this process took a few decades to develop, in these new locations gentrification is occurring at an astonishing rate.

Lisbon — this “new Berlin” 6 — went from a discreet and decadent (but to a certain extent poetic) bohemian lifestyle to a teeming and dynamic city (although considerably more oriented towards consuming and entertainment, in the situationist sense of Guy Debord). We therefore have a city that is changing, up the hill, down the hill, with an impact that has been felt on an architectural and urban level, wherein it is curious to observe the way in which these two levels are interlinked in terms of practices, choices and visual aesthetic and spatial trends.

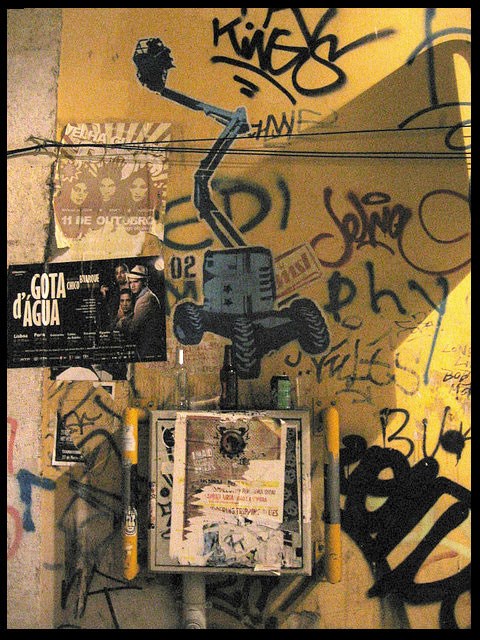

Over the last few years the Lisbon Municipality has executed important renovations in various infrastructures of the city, namely the main roads and squares. However, a large part of Lisbon’s important urban projects, which included the construction of several new buildings by internationally renowned architects, such as the ones for Parque Mayer (Frank Gehry; Aires Mateus), Alcântara XXI (Aires Mateus, Frederico Valssasina, Jean Nouvel, Álvaro Siza, Mário Sua Kay) or the Braço de Prata gardens (Renzo Piano), were stalled when the financial crisis hit 7. Thus, different types of urban intervention solutions emerged, more ephemeral and erratic, at times superficial or simply aesthetic, mostly destined to attract the attention of tourists. Street art is an example that reflects this attitude. By intervening in walls and facades of so many of the capital’s buildings, they place the city among the international subset of alternative tourism. On the other hand, in terms of urban intervention, street art serves as a disguise to detract attention from problematic situations such as the degradation of buildings.

© Fernando Aranda

Does “Re-architecture” still have any critical value in terms of spatial interventions and urban policies? Among the alternative cultural spaces that resort to these types of re-architecture practices there are well-intentioned and effective uses, with concerns that reflect the desire to participate, intervene and help to re(construct) the city. Yet in certain cases, there is also the appropriation of the aesthetic and visual symbolism of counter-culture, resistance movements and urban struggles (that fight authoritarian, repressive and intolerant forms of spatial domination) that reveal to be excessive. There is a deviation from the original content of these symbols, these visual and spatial references, which can be detected by production conditions with a commercial logic of these same images and spaces (against a logic of organic, participative and transformative production).

According to the architect and critic Manfredo Tafuri, many of the interventions in the city are guided by the laws of profit: “The architectural, artistic and urban ideology was left with only the utopia of form as a way of recovering human integrality through an ideal synthesis, as a way of embracing disorder through order” (Architecture and Utopia – Design and Capitalist Development, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1976, pp. 46, 48). This “disorder” can be found in the Cais do Sodré area, in the physical condition of certain pre-existences – which in the case of Pensão Amor is expressed in the stairwell, and in the multiple old objects and furniture spread throughout the interior of the building – or in the festive environments of nocturnal spaces that spread out onto the street, and in the consequences left behind on the street after a crazy night (glass from broken bottles, uninviting smells, mistreated urban furniture) 8. This “order” is present in the existence of security guards at bar doors and the presence of police on the street, and is particularly present in the conception of the projects themselves: vertically, designed by the collaborators of the promoting companies, and not spontaneously and horizontally, developed by its users throughout time, as the final result suggests. The “order” is also found in the implementation of the terraces, along the street, using separation ropes, contributing to the increasing privatization of the public space.

Going down, going underground? Could it be that having gone down the hill, the celebration of alternative culture (artistic, architectural, musical) has moved, or has there been an accelerated and accentuated propagation of the phenomenon of gentrification and touristification?

© Letícia Carmo

One of the Bairro Alto’s “trademarks” were the tagged facades, easily identified in photographs or other types of images. After undergoing a cleaning process (activated by gentrification and touristification), these walls became more sterile, like any other wall in any other part of the city, no longer a characteristic of this specific festive environment, free and spontaneous, of that neighbourhood’s own. Conversely, the walls of Cais do Sodré and of the more recent areas of “alternative” cultural celebration were not attacked by rebellious tags when the ones in Bairro Alto were cleaned – outlawed by municipal services. Those walls, and the pavement, were coloured with murals by invited artists, sponsored by institutions and especially by companies, framed into specific urban rehabilitation and regeneration projects (ex.: areas of Intendente and Alcântara).

We can conclude that “alternative” culture — inspired by revivalist, artisanal and counter-culture aesthetics — has become quite appreciated and generalized, becoming a significant part of the visual physical urban environment. Its process is linked to the geographical and economic changes of the city (and the world), which stimulated the need for more economically modest and ecological solutions, conditioned by the politics of austerity. However, the essence of the rebellious and subversive content specific to an alternative culture changed, becoming less radical and incorporating projects of a more commercial nature. ◊

© Letícia Carmo

Other bibliography and sources

Carmo, Letícia (2016), Resistance & Compromise – Spatial & Aesthetic approaches of Alternative Cultural Spaces in Lisbon, Ljubjana & Geneva, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (available online: https://infoscience.epfl.ch/record/223448).

Florida, Richard (2002). The rise of the creative class : and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

Landry, Charles (1995). The creative city: A toolkit for Urban Innovators. London: DemosOrganisation.

Landry, Charles (2006). The art of city-making. London: Earthscan.

Rainha, Luis, Mateus, J., Caetano, P., Pereira, R., Fernando, E., Jeremias, L., & Ramos de Almeida, N. (2000). Noites de Lisboa - atribulações, deambulações e outras confusões. Lisbon: Má Criação

The dissertation “Resistance and Compromise: Spatial Aesthetics of Alternative Cultural Spaces in Lisbon, Ljubljana and Geneva” that the author developed, was part of the research project “Creative Cities and Counter-Cultures”, financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation.